Author: Massimo Misley

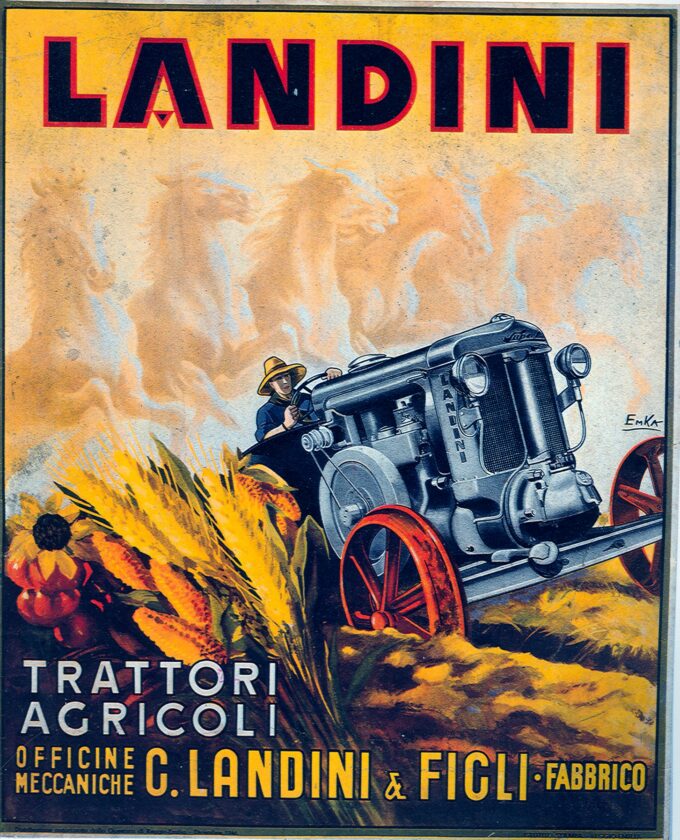

The 1920s of the Last Century. In the 1920s, after the first appearances of Fiat and Pavesi-Tolotti tractors powered by petroleum engines, it was time for the Bubba, Orsi, and especially the Landini tractors—manufacturers that offered single-cylinder, hot-bulb engine tractors to the market. These were rustic, robust engines capable of burning heavy, low-grade fuels that were cheap, making them ideal for that historical period. The hot-bulb engine itself was not a brand-new invention; it had been patented by British inventors Akroyd and Binney in 1890, used on a Hornsby-branded tractor by 1896, and produced on a large scale by the German Lanz and the British Marshall companies. Despite their rather modest performance, Italian hot-bulb engines, simple and affordable, dominated the market until the outbreak of World War II, contributing to the extensive land reclamation work that turned Italy’s marshlands into arable land. A notable leader in this field was Landini, a company founded in Fabbrico, Reggio Emilia, in 1884 to produce winemaking machines and that only in 1925 launched its first tractor, the “30” model, which went into series production in 1928 with a unique construction design.

One of the First Bearing Frames

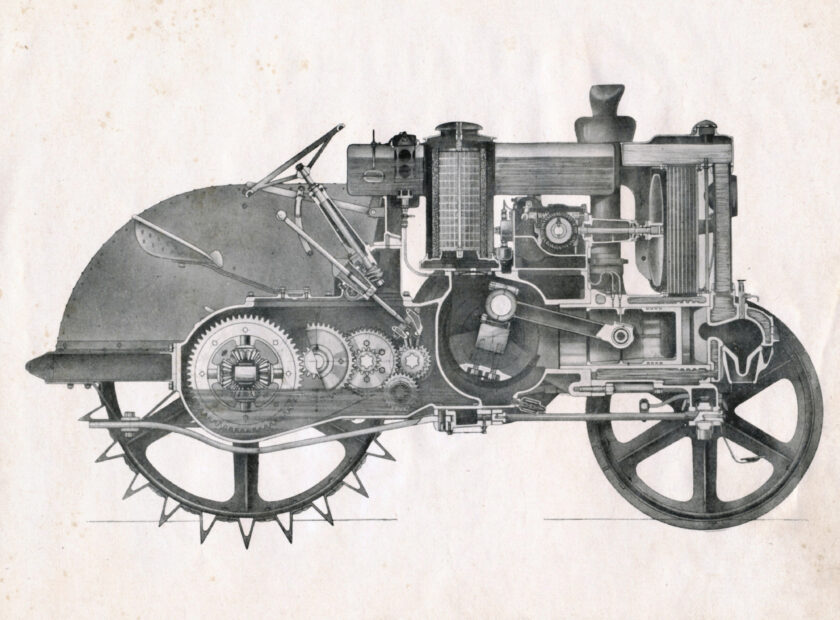

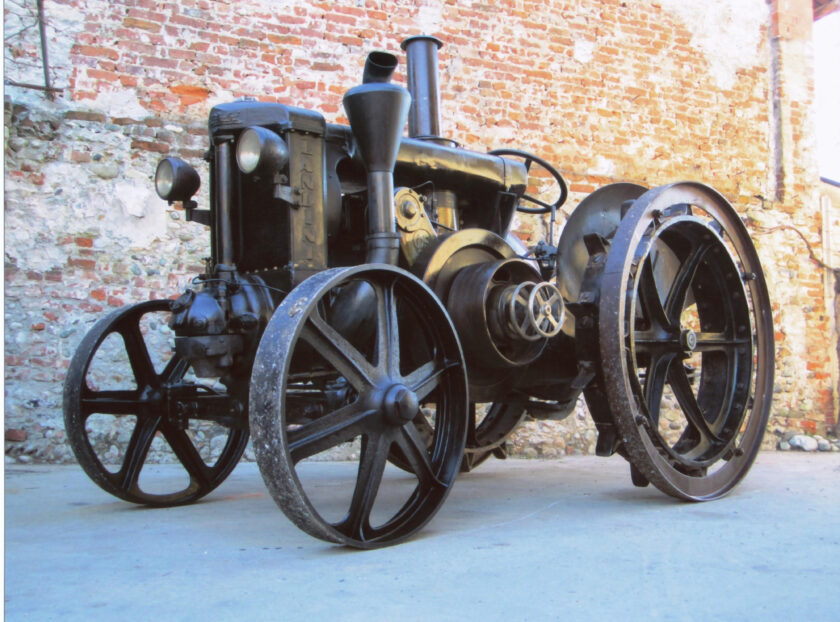

While most machines of that time were built with a frame that supported the engine and other components, Landini developed a bearing frame by integrating the transmission and engine. This engine was a hot-bulb type with 11,770 cubic centimeters, producing 25-30 horsepower. It was a high-performance machine for its time, so much so that four years later it was followed by the “40” model, and in 1934 by the “SuperLandini” or “SL 50.” Weighing 3,500 kilograms, 1,730 millimeters wide, 1,830 millimeters high at the exhaust, and 3.35 meters long, the “SL 50” inherited the basic design concepts and some components from the “40” model, such as the shell-shaped fenders, the injection pump, and the six-spoked wheels cast in an outward-curving design.

The throttle control, located next to the gear lever, and the diameter of the flywheels were also the same, though the latter was later reduced. The round screw-top water tank cap, similar to that of the fuel tank, was also prominent. Despite these similarities, the “SuperLandini” was something genuinely new compared to previous models, with features such as a radiator with a thermosiphon system and a new overall layout. The fuel tank connected the radiator to the driver’s position, acting as a hood, allowing for greater space and comfort. The driver sat on a broad, flat platform equipped with a spring-mounted seat, steering wheel, and gear lever.

Over 12 Liters for 48 Horsepower

For improved traction and stability, the hitch point for the drawbar was redesigned compared to the previous model, positioning it roughly at the center of the machine to reduce tipping caused by sudden increases in towing load. The engine had a displacement of 12,208 cubic centimeters, achieved with a 240-millimeter bore and a 270-millimeter stroke, delivering a maximum output of 48 horsepower at around 620 RPM—eight horsepower more than the 40 model’s 500 RPM. Today, this might seem modest, but at the time, it placed the “SuperLandini” among the most powerful tractors on the market, a distinction it held until after the war. Its advantage was that most 50+ horsepower tractors of that time were American: heavy, bulky, complex, less reliable, and challenging to maintain.

Simple and Reliable Mechanics

The “SuperLandini” was vastly simpler, easier to use and maintain, and easy to start. When started correctly, it would always fire up, running for hours under load without overheating or showing signs of strain. Despite its complicated starting ritual, the tractor’s advantages gave it an edge over competitors, and its aesthetics were appealing as well, dominated by the front water radiator, whose fan was powered by a mechanical assembly that also housed the injection pump, regulator, and oiler. This component, a kind of mechanical control unit, was driven by a chain connected to the crankshaft, reducing the need for additional chain or belt connections except for the dynamo needed for nighttime lighting. The engine structure included a cylinder supported by a front axle mount and a housing that, in addition to serving as an engine base, contained the steering box, three-speed gearbox plus reverse, and differential. The transmission clutch was a disc type located inside the right flywheel, activated by a single pedal at the driver’s position, as the brake was hand-operated with a lever acting on the transmission. This setup was later complemented in road versions by brakes acting on the rear drive wheels, aided by a compressed air system. The gear lever was secured by a safety lock that could only be released by pressing a knob on the lever, granting access to three speeds, with the shortest achieving a speed of three kilometers per hour and the longest slightly over six.

Iron Wheels for Road Travel

Minimal performance, but fitting for a machine that was initially delivered with clawed iron drive wheels, which required the addition of iron rims for travel outside the field.

More than satisfied with the success of its hot bulb tractor, in 1938, Landini decided to revise the machine by launching a second series, which could be easily identified by the new, integrated “Roman chariot” style fenders. These extended to the front, forming a single unit that fully protected the operator. The spokes of the rims were given a more vertical configuration, and the screw cap on the water radiator was replaced with a “door-style” element with a spring-loaded safety closure. The diameter of the flywheels was also reduced, the throttle control was moved to the left fender, and the toolbox shape was modified. It’s important to note that, at the time, for many manufacturers—including Landini—there was no clear line of demarcation between the first and second series of a machine due to the relatively limited production volumes. For example, in 1937, the company produced a total of 164 “SuperLandini” and 99 “Velite” tractors, and parts in stock from one series or another were used as needed.

Parts from the first series could be found on later models, if necessary, and vice versa for components undergoing durability tests. Further complicating historical reconstructions of differences between the two series, many surviving models have been restored or completed with pieces from both series. However, the second series did offer a more spacious operator’s platform, with simpler control organization, placing the throttle and brake lever on the left, the steering wheel and gear lever in the center, and the clutch pedal on the right. The only electrical component was the dynamo switch for faint nighttime lighting. There were no gauges, but fuel levels could be monitored by a rod emerging from the tank, which a floating element pushed up or down depending on fuel levels, while the lubricating oil level could be checked through a transparent window on the engine unit. When running at full power, the machine consumed just under 12 kilograms of diesel per hour, dropping to eight or nine with average daily use.

Low Fuel Consumption but High Oil Usage

The 85-liter fuel tank capacity provided a reasonable work range, but oil consumption needed monitoring, as it approached two kilograms per ten hours of work. This lubricant also tended to accumulate dirt and lose its properties. Consequently, from 1940, an oil recovery system with a filter was introduced, though it now required frequent checks and cleanings. Despite these maintenance demands, shortly after World War II, Landini increased the tractor’s maximum power to 50 horsepower at the pulley, achieved by raising the RPM to 650 and adjusting the injection pump.

This increased fuel and oil consumption slightly but also enhanced the machine’s reputation, making it even more “Super” and featuring an identification plate indicating the tractor type and serial number, as well as the shaft power, effectively equal to the pulley’s power. The label “CV. 45.50” was not shared by many other machines, and it mattered little that the first figure referred to continuous power and the second to peak power, available only when needed and for a short time. It is no coincidence, then, that the machine achieved unprecedented market success, with over 3,300 units built from its launch in 1934 until 1951. This success was also driven by the company’s consistent updates to the tractor, including a post-war option with pneumatic wheels, offered at an additional price of 250,000 lire. The simple, clean, and reassuring look also contributed significantly to its positive reception among customers.

Hot Bulb

The name “Testacalda,” or “Hot bulb” in English, originates from the distinctive ignition system of the engine. Since combustion pressure did not produce sufficient heat to ignite the fuel as it does in diesel engines, and since the fuel was often low quality, it was sprayed against the wall of the combustion chamber, which was preheated by an external kerosene lamp for about ten minutes. Once the chamber was hot, a small amount of fuel was injected manually, the large piston was brought to top dead center, and it was rocked by force on the flywheel until the engine, after a few bursts, started. The process was complex, laborious, and even dangerous, yet there was a thrill in hearing the uncertainty of the first explosions, watching the tractor shudder as if it had a life of its own, before it settled into a familiar, steady rhythm like an old friend.

| SuperLandini in sintesi | |

| Motore | t.calda orizz. |

| Cilindrata (l) | 12,2 |

| Potenza (cv/rpm) | 45-50/650 |

| Raffreddamento | radiatore/ventola |

| Marce | 3+1 |

| Velocità (km/h) | 3,8/7,8 |

| Passo (mm) | 1.900 |

| Lungh. (mm) | 3.100 |

| Largh. (mm) | 1.720 |

| Altezza (mm) | 1.600 |

| Peso (kg) | 3.200 |

| Produzione (da/a) | 1.934/1.951 |

| Matricole (da/a9 | 1.501/6.868 |

| Produzione (n.o) | 3.234 |

Title: Testacalda SuperLandini, super in every sense

Author: Massimo Misley

Translation with ChatGPT